A Conversation with Matt Hill, Author of Graft—Finalist for the Philip K. Dick Award 2017

Matt Hill’s novel Graft is a finalist for the Philip K. Dick Award 2017.

It’s incredibly timely to post this conversation—originally published by Strange Horizons under the title Manchester, A Tale of Two Dystopias—because of two exciting events:

Last week, the Philip K. Dick Award announced that Matt’s novel Graft is a finalist for the 2017 Award. Many congratulations, Matt!

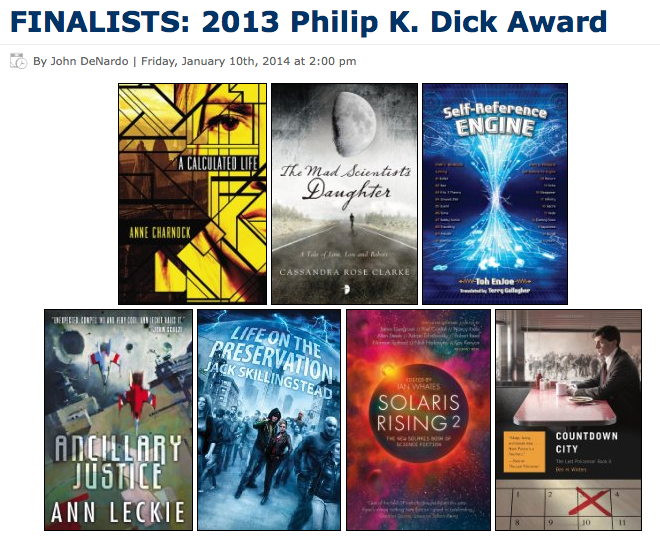

And in two weeks’ time, NewCon Press will publish my novella, The Enclave, written in the world of A Calculated Life—itself a finalist for the Philip K. Dick Award in 2013. You can pre-order the Kindle eBook or Paperback/Limited Edition Hardback 🙂

Read on…

Manchester: A Tale of Two Dystopias

Anne Charnock grew up in Bolton, Greater Manchester. Her debut novel, A Calculated Life (47North, 2013)—a corporate dystopia set in Manchester—was a finalist for the Philip K. Dick and Kitschies Golden Tentacle Awards. Sleeping Embers of an Ordinary Mind (47North, 2015) is her second novel (Dreams Before the Start of Time will be published in April 2017). Find Anne on Twitter @annecharnock.

Matt Hill was born in 1984 and grew up in Tameside, Greater Manchester. He is the author of two novels set in a collapsing near-future Manchester: The Folded Man (Sandstone Press, 2013) and Graft (Angry Robot, 2016). You’ll find Matt on Twitter @matthewhill.

The following discussion took place at Mancunicon, the 67th British National Science Fiction Convention, on 27 March 2016, as a panel item titled “New Visions of Manchester.” The transcript has been revised and edited for publication.

Anne Charnock: Matt and I have been paired up for this conversation because we’ve both written novels set here in Manchester. They’re both dystopias, both set in the near future. So there’s a good deal of overlap. But in other ways we’re very different writers, and our novels are set against our personal histories and our particular connections with this city.

I’ve had two novels published and have a third in the works. My first novel, A Calculated Life, was originally self-published but it was picked up by 47North, edited and re-issued in September 2013. Much to my surprise it was shortlisted for two awards, the Philip K. Dick Award and the Kitschies Golden Tentacle for debut novel. My second novel, Sleeping Embers of an Ordinary Mind, came out last December. Dreams Before the Start of Time will be released in April 2017.

My connection with Manchester came early—I was brought up in Bolton. I expect some of you are from down south so let me explain. Bolton is a big former mill town lying ten miles northwest of Manchester. When I was growing up it was still very much at the heart of the cotton industry, supplying Manchester. It was quite common for us to visit the moors above the town and look down into the Bolton basin. You’d see so many chimneys. But as I was growing up that scene gradually changed. The chimneys started to disappear. When I was in sixth form, I had a job at one of the old mills, but by then it was a warehouse for a catalogue company. The whole region had changed.

I moved away from the North West for sixteen years or so. I studied environmental sciences at the University of East Anglia, and went into journalism in London. Eventually—this would be the late 1980s—I came back up north, and at that point I decided to change career. I’d been working in journalism with photojournalism, and enjoying it, and decided it would be interesting to follow the creative path. So I enrolled at Manchester School of Art, started a degree, and went on to do a master’s in fine art. I reconnected with Manchester, commuting in every day. At the end of my master’s I looked for studio space, and several of my MA colleagues and I got together and founded a studio group in Salford, Suite Studios, which is still active today.

Matt Hill: It’s interesting that you talk about coming back, because that’s been important in my writing. I grew up in East Manchester, about ten miles out towards Glossop, in a very small village called Mottram, then later lived in Hyde. When we were in Mottram, mass murderer Dr Harold Shipman lived in the village, and League of Gentlemen was filmed just down the road, and so part of me does wonder if writing dystopian fiction was inevitable . . . Eventually I left Manchester to study journalism at Cardiff University, and I stayed down in Cardiff for six years, swearing I’d never go back to Manchester for one reason or another. Then, after all that, I went back to Manchester anyway. I stayed put until 2012, when my wife and I moved to London for day job stuff.

I suppose having those ten years away from home, from Manchester, has made me mythologise the city, reconfigure it in my mind. Being distanced from the place allowed me to write about it. So while my connection to Manchester is obviously an accident of birth, it’s still gone into my work. We’re actually moving back up north in June, and I question whether that will prompt a shift in focus. Maybe I’ll want to write about London.

AC: Perhaps you could talk about how you got into writing, Matt. Did you start writing as a teenager, or during your time studying journalism—when did that creative side of things come in?

MH: When I was much younger, I used to play a lot of Warhammer 40K. I say play—I never actually had anyone to play it properly with, so I’d paint the figurines and then make up stories for them. I was too shy to go along to Games Workshop, so I’d write all these imaginary battle reports. That was probably the start of something. Another influence would have to be my grandparents, both brilliant anecdote-tellers, whose love of books rubbed off.

My first “serious” attempt at writing fiction was a novel about a time-travelling agony aunt called Marigold. I should say I’d actually written two-and-a-half novels before The Folded Man, which became my first published book. Marigold’s story was one of these, and it was partly based on this silly agony aunt column I wrote for the student paper at university—I was completely anonymous, but the point was that everything I suggested made problems worse. I cringe to think about it, never mind read it back, but it was a lot of fun. Someone told me I should try some fiction like it, and so one thing led to another. It was massively overwritten, and I’d be mortified if anyone saw it now, but it was a go at a novel-length piece, and I remember thinking, this is terrifying, but it’s not as impossible a task as it seems when you’ve not done it before. How about you?

AC: It took me a long time to come around to writing. I wish I’d started early, as you did. I’d always studied maths and the sciences, so English and the arts were left behind quite early. I can remember thinking during my journalism days, I wonder if I could write a novel? And I immediately dismissed the idea. I thought, no, I could never write that many words. In journalism you’re writing 100-word pieces, or 200, maybe 1,000, which is the longest the nationals would take. The longest piece I ever wrote in journalism was 4,000 words, which was the standard length of a long feature in New Scientist. So I really didn’t think I had enough words in me for a novel.

MH: So was it quite freeing when you realised you could write something with as many words as you wanted?

AC: No, I was terrified! I was terrified that I’d never reach anywhere approaching novel length. When I started to shop around my first novel, one agent replied to me saying, I can’t possibly sell this book to a publisher, it’s too short. To reach the point where I felt I could attempt a novel, I had to completely re-educate myself. It was only by studying fine art that I unlocked the creative side. I just didn’t have the confidence to write fiction until then.

MH: And that was in Manchester. Do you think it was because your life there was a bit more free?

AC: You should be a psychiatrist! Yes, you’re right. Coming back to Manchester, taking a foundation course, the degree and ultimately the MA—it was a huge revelation to me that I could be what’s called a creative person. I’d always been a very grounded journo type. This is the job, write this many words, write the captions, find the photographs, move on to the next job the next day.

During the final year of my master’s, my tutor was looking at my studio work, which dealt with the difference between human intelligence and machine intelligence, and he said—why don’t you try to say what you’re trying to say in a piece of short fiction? So, just as you were prompted with your column, Matt, I needed a prompt, to have a go. I wrote a couple of short stories over the next fortnight, and thought, I should have been doing this a long time ago.

MH: How much did your time being a journalist equip you with the skills to write fiction?

AC: Reasonably well. I can string a sentence together, and I can write concisely. Maybe sometimes too concisely. When you’re a journalist the aim is to submit a piece of copy that the section editor can’t edit, that they can’t reduce by a single sentence. You want the subeditors to be mad with you because they can’t trim an inch off the end. I find it difficult to shed that mindset—I’m writing fiction thinking, well, that sentence can go! I’m really envious of writers who write long, who write 120,000 words and then cut 30,000. I can’t imagine ever being in that situation. For me it’s the opposite. I’m looking for where I might add words. I’ll say to myself, I suppose I could add 200 words there . . . If I’d studied English literature I don’t think I’d have done myself any favour. I needed the art course, that creative outlet, to be able to move on to writing fiction.

Let’s move on to our books. I was impressed by the blurb that describes Graft as “some combination of Raymond Chandler, Trainspotting, and Philip K. Dick.” What I admired when I started reading Graft was the way you introduced your characters in short order through several short chapters in the first twenty pages or so. You introduce Roy, who’s a hitman, Y who’s posthuman, and Sol and Irish, who are running a car workshop. They’re all very distinct. And I felt total confidence that you knew what you were doing. I could relax. But Graft is a very visceral read, perhaps neo-noir, very different to my book, and I wondered: what was it about your experience of Manchester that made you write such a dark book?

MH: I often think, as someone from the area, that I should be showing why Manchester’s great. In the popular mindset, it’s still pretty grim up north—Manchester doesn’t need any more grim fiction. So adding to that pile is probably a bit irresponsible. But Manchester’s what I know, where I know, and it’s a place I love. And so I have to go with the idea that you sometimes hurt the ones you love, because there’s probably something in that. Mainly, though, Graft and The Folded Man came initially from the disconnection, the dislocation, of coming back from Cardiff to the suburbs where my mum lives, and staying there for a while with this feeling I’d never left. And then my early memories and experiences count, too. I remember Manchester being a sort of grey and red-brick monolith, which is actually incongruous with reality, especially with the development post-IRA bomb. But the IRA bomb was one of the defining moments. Harold Shipman being arrested was one of the defining moments. These things seep in. And being older, I was also seeing more sides of Manchester—I was going to local pubs and there’d be kids in the toilets doing really cheap cocaine because that’s what had flooded the market in these little suburb towns.

This mixed with my neuroses about the grim trajectory of things, socially and politically, and all of that went into The Folded Man, which was published in 2013 and depicts a broken Manchester in 2018. Graft isn’t a direct sequel, but it returns to that same world about seven years on. It’s set in 2025, where everything that could go wrong, has gone wrong. Though I wouldn’t say it’s fully post-apocalyptic, it takes place in a country that’s been riven by austerity, by riots, by terrorism, by something close to civil war. A kind of apocalypse in slow motion. That said, the main focus of the Graft is quite myopic, in that it doesn’t focus on the wider picture. It’s about four characters who’ve been thrust into a very challenging environment and are now trying to find their way through it, holding on to what little of their humanity they have left. Meanwhile, other people are—as people tend to do—taking advantage of a bad situation to further their own ends. It’s pretty stark.

AC: It is, but at the same time I felt sympathetic towards these people, doing what they have to do to get by. You’re not down on everybody. I can imagine people facing those choices.

MH: Let’s turn the tables and chat about your work, and its links to the city. How does your experience of the North West and Manchester come through?

AC: I did wonder initially if I should set A Calculated Life, a corporate dystopia, in London? That seemed to be the default. I considered Manchester, but I wasn’t at all sure because I was thinking in terms of readership. But I reached the conclusion that Manchester was an excellent setting because my story hinged on innovations in the field of genetics. I thought, the contraceptive pill was invented here, the first test tube baby was born in Oldham. Manchester is historically a centre of innovation. We had the industrial revolution, the first railway stations, the first programmable computer, the atom was split here, and more recently we’ve isolated graphene. So it made sense that future innovations in genetic engineering would happen here as well.

In addition, at the time, I was commuting from Chester into Manchester and there seemed to be a permanent cloud above the M56. It rained every time I drove to and from Manchester. And that led me to think about climate. I do have some involvement with the climate change lobby. I’ve been involved in a project in my own village, the Ashton Hayes Going Carbon Neutral Project, for the past ten years, and I’d studied at UEA with its climate research unit. So I was thinking, wouldn’t it be interesting to set my dystopia in a region that turns out to be a climate change winner? So climate change forms a backdrop to the story, though it’s not a major theme, and the North West has become the new Tuscany. In the novel, farming has moved away from rain-fed agriculture, cereals, and livestock, towards irrigated citrus, vineyards, and olives. That was my thinking, to create a different feel, to have the North West as a climate change winner, acting as a foil to the dystopian element of the story.

MH: I think it’s interesting that on the face of it, at least, the Manchester in your book is beautiful. It’s clean, it’s shimmering glass spires, precise little patches of grass, with history sandwiched into it.

AC: And although I call it a dystopia, it is nuanced. Everybody can convince themselves they’ve got a reasonably good deal.

MH: Which I think is a lot more disarming than the collapse scenario in my stuff. Reading your book, it’s plausible. It feels more like where we’re heading: super-corporate entities and everything being about saving more money, being more efficient. Your main character, Jayna, is essentially designed to help the corporate machine achieve this. And so, to me, it’s also about fears of automation.

AC: It grew out of reading Ray Kurzweil’s The Age of Spiritual Machines during my art studies. He argued that in the future there could be a species schism, with augmented humans on one side of that schism. What really got to me was this: he suggested that two people on either side of that divide wouldn’t be able to hold a meaningful conversation. That really frightened me, because I could almost believe it. So I decided to write the novel about what it is to be this person who is so intelligent. I wanted to see if this new world would be as bad as I feared. The story came out of that worry. Jayna is super-intelligent, genetically enhanced, parachuted into the best job in the company. She’s one of a new generation of workers who are employed at high levels in the corporate sector and in the civil service, able to crunch and absorb a mass of information. And she has quite a nice deal. She gets free accommodation, she has all her meals supplied, she doesn’t have to worry about necessities. But she also has real restrictions, such as, she can’t go outside the city limits.

MH: Some of the conflict in the book comes from Jayna being so good at her job, because the people she’s replacing resist her, resist what she stands for. I suppose that’s what I found most interesting: you were exploring a big issue that’s coming down the road.

AC: You’re always looking for a battle, aren’t you? You’re wonderfully attuned to thinking about more visceral stories. Whereas I imagine we’ll drift into this, sleepwalk into dystopia.

MH: Quite possibly!

AC: In the book the unaugmented people are like you and me, organic humans, and they live in enclaves. I wrote this before the bedroom tax was introduced, and in a way the enclaves are the ultimate expression of that governmental mindset—the people on low income, pushed out to the edges. And yet even in the enclaves they have subsidised housing, free energy, free transport. Their lives are fairly grim, and there’s no social mobility, but on the face of it, it’s not all that bad day-to-day. Everyone is rubbing along thinking, I’m OK.

MH: I wanted to ask you another question about Manchester. Obviously the city is growing all the time, new towers going up; the building we’re in now [the Beetham Tower] is visible for miles around. The cityscape is changing, yet it’s distinctive. But in A Calculated Life—as opposed to my novels, where much of the city has been blown up or repurposed—you talk about Manchester in quite anonymised terms. At one point you even use the phrase “downtown Manchester,” which isn’t a phrase anyone living here right now would use. I read it as a sly comment on the future of the city, on it becoming more homogenous. Is that how you saw it?

AC: I saw it being physically stratified: the busy shiny metropolitan core, the suburbs, and the enclaves. It was a way of emphasising the differences between people, having them located and living in different places.

MH: Well, one of the reasons we’re leaving London is because we’ve essentially been priced out of the area we’re living in. There’s a lot of talk—metaphorical, at least for the moment—of walls around London’s inner city. It’s like you’ve made that happen.

AC: Yes, that’s what I was suggesting. What are your thoughts about writing the city as a character?

MH: On making the reader feel the location coming through, I think these days you can get away with writing the geography of a city just by going on Google Maps. And for certain sections of the new novel I’m finishing up, that’s exactly what I’ve done . . . but I don’t think you get the spirit of the place, that way. I think for me, having lived in Manchester, it’s the anecdotes and experiences that stick, and they come out in ways that simply wouldn’t work if I were to set the same story in London. When you really know somewhere, I suppose you could say there’s a conviction, a confidence, and then you have your job of convincing. I’m squeamish about saying “the city is a character,” but I’m also aware that to, say, an American reader, Manchester is not very well known, so there’s a sense of wanting to write it as a character, with the depth of a character.

AC: I find city-as-character quite difficult. On the one hand I did want the story to be convincingly of the North West, but on the other hand there are readers who don’t like too much name-checking. I have a close friend who’s lived in Manchester, and she said she’d have preferred me to set A Calculated Life in a completely fictional city. But I couldn’t do that, I’d much rather have it grounded.

MH: And as we were saying about making myths of a place—if you actually tried to join up the places in my work it would likely be a mess; I’m basically lying about certain things being close to certain places. But then I think having some landmarks name-checked is important for a sense of place.

AC: I do feel we have quite different writing styles. I was asked once if the pared-back style of A Calculated Life was a deliberate choice, that it suited my main character, or whether this style was simply the way I wrote! Truth is, there was an element of both. It suited the story, but I do naturally write pared-back prose.

MH: I thought there was something clinical about it, something efficient, that suited the story. Knowing that you were a journalist, I can see that precision in there.

AC: Whereas your style has that neo-noir feel, so I wanted to turn the question around. Is that how you write, or was it just for this novel?

MH: I think it’s partly the way I write, yes. My influences popping up. But in some ways Graft is pared back as well. When I was writing it, one of its characters, Roy, was initially written in full Mancunian dialect, with the missing words, missing letters, inscrutable slang. I softened that a fair bit in the end, which was the right thing to do. But I enjoy the richness that comes with dialect.

AC: In your next novel, are you writing in that same voice?

MH: Yes, I think I am. But the subject matter is very different in my new novel, because I’m moving away from the world of the first two novels to a Britain in which things aren’t quite as bleak. At least not societally. How about you?

AC: I was conscious before writing Sleeping Embers of an Ordinary Mind that I needed characters who wouldn’t suit that pared-back voice—a way of stopping myself from writing the same way. So I created two thirteen-year-old girls as characters, which necessitated different voices. I enjoyed the openness of it. And yet, I’m still quite concise. I’m still looking at the word count.

To finish off, Matt, what are you working on at the moment?

MH: So far as Manchester goes, I’ve just done an interesting collaboration with a Taiwanese artist called Yu-Chen Wang, at the Museum of Science and Industry. She wanted to explore the inner worlds of some of the pieces in the museum’s collection; what it would be like if you gave certain machines human qualities. She asked me to help with the stories, which was challenging, but really satisfying. And it was exciting to write science fiction as a collaborative thing. What about you?

AC: I’ve nearly finished my third novel, Dreams Before the Start of Time, which will be published next year. It considers how relationships might change with the advent of new human reproductive technologies—artificial wombs, parthenogenesis, stem cell-derived eggs . . . different possibilities for making babies. I’m imagining the fallout, the negatives and the positives.

Thanks so much for the conversation, Matt—it’s been fun!

MH: Thank you!

And many thanks to Niall Harrison for editing the transcript of our conversation for Strange Horizons.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!